Picture this . . . It’s late afternoon on a gloomy, overcast Friday. Coming to its end is what has been a marathon day of professional development designed to accommodate an entire building staff’s various interests and professional growth goals (a design that incorporates six one-hour professional development sessions for six different teams of teachers into a single day—whew!). And yet I ended that day energized, pumped, primed, and ready to do another six sessions.

Not being one to leave a good thing alone, I wanted to know why. (And no, gentle reader, it was not because each session involved one teacher and me in pleasant conversation over coffee and doughnuts.) And then it struck me . . .

As coaches and teacher-leaders, we spend a great deal of time and energy encouraging teachers to focus on engagement, on intrinsic and situational motivation, on the different ways we can get kids excited about topics and subjects that are not naturally motivating to many students. We cannot expect all learners to be excited by linear equations or Romantic poetry or the French Revolution. But, we impress on teachers that there are ways to motivate students outside the specifics of the content.

So why, it occurred to me, don’t we always afford the same courtesy to teachers in professional development? And more important, what happens when we do? The answer was residing in that Friday marathon of professional development.

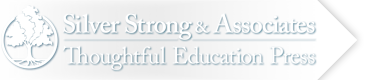

On that Friday, we started each session with a tool called a Learning Window to lay out the outcomes we expected to achieve (see photo). Each session’s Learning Window was really simple: We were going to look at controversy and curiosity, two situational levers that we can use to stimulate student interest and increase engagement in any classroom. And we were going to explore instructional tools for generating controversy and piquing curiosity. This exploration of tools included tools teachers had already implemented after our last session and were now eager to discuss, along with new tools we were going to learn together in our Friday session.

We framed this focus as a study in energies—energy in the classroom, energy of the students, and energy of the teachers. And so I asked the teachers if they could recall a day when they left school with more energy than they had when they arrived.

After some giggles one teacher, who had been working really hard to engage his students, said, “These tools have helped me rethink how I teach—I may never retire.”

And with that we were off and running. In a moment that reminded me a bit of When Harry Met Sally, one teacher called me over to say, “I want what he’s got.” By the time the first session was finished, participants had reviewed a number of instructional tools, chosen one they would commit to using at least twice in the next three weeks, posted their choices, and thought through their initial ideas for implementation with the help of their colleagues.

So it went for all the sessions that day. We laid out our goals, discussed teachers’ experiences with tools they had used with an eye toward refining practice, selected new tools for increasing engagement in the classroom, and planned for classroom implementation.

What struck me most about that day was the way in which the teachers worked together to help each other find the right tools for their unique situations. Each session turned into a set of informal learning clubs, with teachers forming small teams focused on solving their particular problems of practice. For example, one teacher expressed interest in the tool called Window Notes, which is designed to get students actively involved in creating notes that include facts, questions, personal connections, and reactions to the content under investigation. But she was concerned about how to keep students’ notes focused without diminishing the energy that the tool can help create. The teacher sitting next to her suggested that students needed some guidance on how much to write. Based on his experience with the tool, he recommended four facts, three questions, two reactions, and one connection.

Other learning clubs worked more directly with me to find the tools that would address their particular challenges: “I’m helping my students learn to find textual evidence when they read, but to be honest, it gets pretty boring. Is there a more engaging way to help my students build this critical skill?” (Answer one: Yes. Answer two: A wonderful little tool called Scavenger Hunt [LINK to Tools for a Successful School Year].)

Still other teachers were looking for ways to use the tools in their unique situations: “I am a resource room teacher. I am a physics teacher. How do these tools work in situations like mine?” I was especially energized when one teacher showed a physics teacher how the tool called Questions Are QUESTS is ideal for helping students think through challenging physics problems.

A critical element across all of these sessions was choice. The teachers were engaged because they were able to make real choices about how to motivate their students. What’s more, they had practical tools to choose from, and they were able to work collaboratively to make their choices work in their classrooms.

I have always believed in the power of choice. And this experience for me served as an affirmation of just how powerful choice can be, not only for students in the classroom, but also for adults pursuing professional learning.

Stay tuned—I will report back after my next visit and let you know what kind of impact this kind of choice had in empowering teachers to act on the commitments they made on that gloomy, Friday afternoon.